This week saw a 258-page Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities report published in the UK. It declares the UK no longer has a system rigged against ethnic minorities. Pat yourself on the back, Britain and grab a glass of prosecco; we’ve fixed institutional racism! Considering the Macpherson Report at the end of the last century claimed the UK is institutionally racist, which was a widely accepted fact, we’ve done incredibly well. For those not familiar with the Macpherson Report, the report followed the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, which involved a racially motivated attack on a black teenager by the police. It announced that parts of the British police are institutionally racist. So, to have abolished institutionalised racism since then is excellent work!

What an absolutely ridiculous thing to say; of course, the system is rigged, and we evidently live in a system of denial. Liz Fekete, the Executive Director of the Institute of Race Relations, summed it up perfectly. She stated, “institutional racism today is held in place by policies, institutions and government spokespeople that deny it exists at all”. After almost a year since George Floyd died at the hands of a police officer, which sparked global protests supporting Black Lives Matter, this report is divisive and offensive. I intend to use this article to prove that the UK is institutionally racist.

What is institutionalised racism?

So what is institutionalised racism? Institutionalised racism insinuates that some intra-institutional rules and regulations favour the majority populace over minority ethnic groups. This is sometimes referred to as unintentional institutional biases. This sort of bias means that people who report that they are not racist might harbour implicit race biases and be influenced by these biases in the way they behave.

Now I’m not referring to that questionable person who states they’re not racist because their golfing buddy is black. No, people who sincerely declare they treat people equally and fairly, and on the outset, probably do. But these biases are implicit and are not always easy to detect, and there are lots of different unintentional biases. For instance, implicit race bias findings indicate that individuals will perceive black individuals as more hostile and that whites will behave with greater hostility in interracial interactions. There are countless stories of people clutching their bags tighter when they pass a black individual.

Unintentional biases

Now, if you are sat there thinking, “I’ve done that”, I’m not calling you a racist pig! I know I have definitely been subject to these biases, but that is why they’re called unintentional biases. We subconsciously learn stereotypes, attitudes, or categorisations. These are automatic, involuntary, inbuilt and often affect our decision-making and behaviour. Some studies conducted by psychologist Patricia Devine show that people tend to have more positive associations with white than black people. Other studies show that black males are more readily associated with weapons and that black males are more strongly associated with danger and hostility. These biases evidence the institutional racism that exists, but this isn’t all my evidence, so strap in!

Racism within the police

As I mentioned earlier, May 2020 saw George Floyd’s death, which sparked the protests supporting Black Lives Matter. The number of times I have read comments or heard people argue that “BLM is just an American thing – there’s no need to bring that up over here” is countless. Covid restrictions in the UK have exacerbated the over-policing of Black communities, and the circulating of some genuinely shocking videos of police brutality should have made it impossible to ignore the harsh realities of racist police violence.

The tasering of Desmond Ziggy Mombeyarana comes to mind, which saw a black NHS worker tasered in front of his 5-year-old son. Another tragic addition to this story is that Desmond’s partner died in 2016. This received national media coverage after a coroner found paramedics failed to provide her with the most basic care and accused her of faking her illness. I think any individual would begin to lose faith in the system. Still, in a local newspaper, a racist commenter wrote, “‘I don’t trust the police’ – the feelings mutual. We don’t trust you either, even less so, in fact. I honestly think some people need to go on a British culture refresher every 5 years. If they don’t shape up, give them the Shamima Begum experience. We don’t need people like this”.

“Black people are 10 times more likely to be stopped and searched”

Tell me again that the UK is not institutionally racist; I’m going to hit you with a few facts. Black people are almost ten times more likely to be stopped by police than white people. Many studies have concluded that stop and search is an ineffective method of reducing violence. Yet, we still await the reduction of state-sanctioned harassment of black communities. Furthermore, what is harrowing is under section 60, which allows police officers to search anyone in a defined area for a limited period without the requirement of “reasonable suspicion”, sees black people outside of London stopped and searched 43 times more than white people. Oh, but the race report described stop and search as a “critical tool for policing when used appropriately”.

Additionally, Inquest’s report presented the breakdown of deaths in police custody and the proportion of Black, Asian and minority ethnic deaths in police custody where restraint or use of force was a feature is over two times greater than it is for other deaths in police custody. Yes, we are slightly better than our cousins across the pond, but the same hegemony of impunity exists. In the United States, 99% of killings by police officers have resulted in no conviction. In the United Kingdom, only one officer has been convicted, receiving a suspended sentence over death in police custody since 1969.

Knife and gang crime

I don’t want to solely focus on the institutional racism within the police, so I will leave it here with one final point; knife crime. Knife crime in the UK and our panic over youth violence has been wholly racialised. Black people are massively over-represented on police gang databases. In Greater Manchester, according to official data, Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic young people are responsible for only 23% of serious youth violence. However, they make up 89% of the force’s gang database. I don’t think we need to find a mathematician to show that doesn’t add up!

“It is difficult not to conclude that young black and minority ethnic people end up on gang databases as a result of racialised policing practices, not because of the objective risk they pose”.

Williams and Clarke, 2016

Scholars and activists have long since argued, and continue to argue, that the depth of racism in UK policing points to a problem that is institutional and deeply locked into policing.

Education

The report also looked at education and stated education had been the “single most emphatic success story of the British ethnic minority experience”. Am I missing something here? Research published in the Education Review shows that Black Caribbean pupils are nearly four times more likely to receive a permanent exclusion than the school population. They are also twice as likely to receive a fixed-period exclusion.

Additionally, the teaching workforce is still overwhelmingly white, and studies have shown teachers’ stereotypes and low expectations, particularly of Black Caribbean pupils. To add, Crenna-Jennings suggested that students with special education needs and disability (SEND) are more likely to be permanently excluded than non-SEND students. When ethnicity, gender and SEND intersect, the most recent data indicate that Black Caribbean boys with SEND are 168 times more likely to be excluded than white girls who are non-SEND. Parsons argues that the disproportionality of exclusions among Black students has been attributed to racist attitudes and stereotyping by teachers and school administrators.

We need anti-racism policies to remove any institutional racism. However, seemingly race-neutral policies can discriminate against ethnic minorities. Take school hair policies, for example. There have been numerous black students being excluded due to their hair not meeting school uniform requirements. These policies are shaped by racialised value judgements on what is ‘neat’, ‘tidy’ and ‘acceptable’, which discriminates against black students.

Why are ethnic minorities remain under-represented at Russel Group universities?

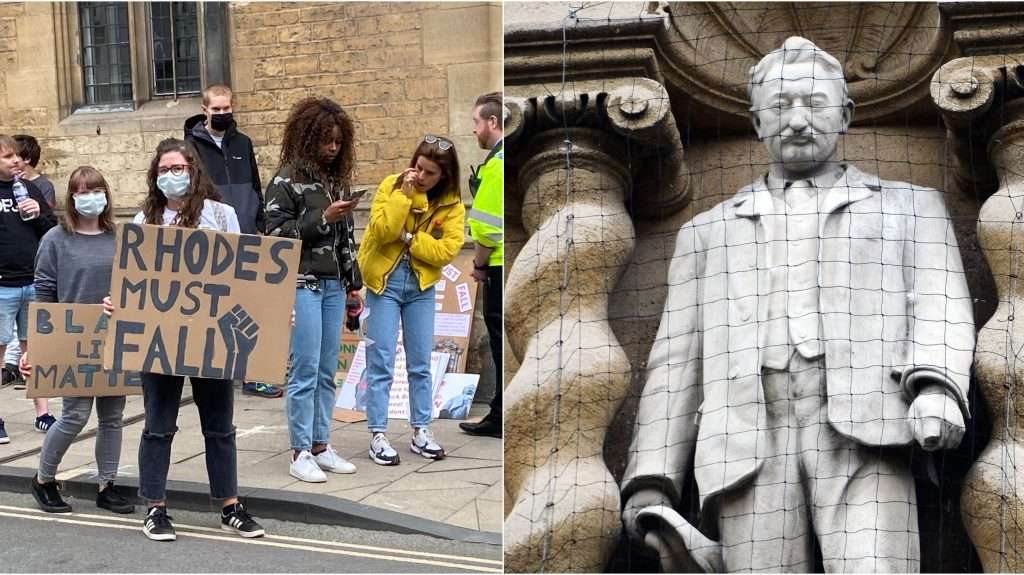

Ok, the race report was correct in stating educational attainment for ethnic minority young people is improving, with Indian and Chinese young people consistently outperforming White British students. So, can you tell me why ethnic minorities remain under-represented at Russel Group universities? Britain’s oldest and most renowned universities have colonial histories inscribed on their campuses and architecture. I’m sure you remember the recent controversy surrounding Cecil Rhodes’ statue at Oriel College, Oxford. How can Cecil Rhodes, a white supremacist, be commemorated in this way and become embedded within the university fabric. No wonder ethnic minorities feel a sense of unbelonging in these places. The evident lack of curricular diversity and underrepresentation of minority ethnic students and practitioners shows white privilege is reinforced in higher education. Those privileged by the system are consequently blind, unaware and often ignorant to their role in the reproduction of whiteness.

Employment

The report also looked at employment and stated that “Ethnic minorities have been making progress up the professional and occupational class ladder, though some more than others, and there remains under-representation at the very top”. Understatement of the year, ladies and gentlemen. Job applicants with British sounding names were more often shortlisted for a job. Surely, this can’t be true. Di Stasio and Heath examined UK employers’ hiring practices by applying for jobs using fake CVs, which differed only by their ethnicity signalled by their name. The results suggested that ethnic minorities needed to send 60% more applications to get a positive response from employers than a white British person, with discrimination exceptionally high against Pakistani applicants.

Ethnic minorities have lower average earnings

A consistent pattern emerges where Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black African and Black Caribbean groups have lower average earnings. Sure, I did just say that fewer minority ethnics go to university, but this is still the case even after differences, such as education, are considered. It cannot be claimed that the observed ethnic differences in pay are wholly the result of a difference in education or the relevant populations’ age structure. The inescapable conclusion is that a significant ethnic penalty exists. The Resolution Foundation found that after controlling for various personal and occupational factors, including age, education, sector, industry and job tenure, black male non-graduates had hourly wages around 9% less than equivalent white workers.

Moreover, the Trade Unions Congress, stated “BME workers too often experience racism at work, which is part of their everyday life. And more times than not, it’s hidden. There are more obvious racist incidents that take place. But also the more hidden types such as micro-aggressions, implicit bias and prejudice”. Additionally, 72% of BME academics have also experienced overt racist bullying and harassment from managers and colleagues, according to a UCU report. Research has found racist practices in recruitment, promotions, and pay in career progression in academic or professional and support services in Higher Education Institutions.

Highest unemployment rates

With all this in mind, is it a surprise that ethnic minority groups experiencing the highest unemployment rates in the UK are the Black Caribbean (10%) and Black African (8%)? To rub salt into the wound, the high unemployment rates among ethnic minority men and women can have disproportionate effects on their welfare, given how the benefits system and the new Universal Credit regime penalise larger families.

But what about the other minority ethnicities? I hear you ask. Well, the report is correct in stating they have found themselves on the employment ladder. However, many studies argue that the low levels of unemployment among the Chinese and the White Irish groups can partly be explained by their high employment rates in routine, low-skilled and poorly paid employment. There are persistent patterns in the labour market that disadvantage ethnic minorities in the UK. So maybe we shouldn’t be so scared about migrants stealing our jobs after all.

Health

Finally, the report did touch on health inequalities. The commission rejected the view that ethnic minorities have universally worse health outcomes compared with white people. I’m still waiting for the punchline for that joke. There is a substantial body of evidence demonstrating that the multidimensional social and economic inequalities experienced by ethnic minority people, including racism, make a considerable contribution to ethnic disparities in health. Looking at employment again, ethnic minority people are over-represented in the NHS workforce. However, only 7% of NHS Trust board members across England are from an ethnic minority group. More than two-fifths of NHS Trusts have no ethnic minority board members.

I know, how dare I say something wrong about the NHS at this moment in time. In fairness, the evidence does suggest that through the NHS, the provision of publicly funded primary care with universal access and standardised treatment protocols has resulted in equality of access and outcomes across ethnic groups. However, there are inequalities in access to secondary health care and dental care and satisfaction with care received. For example, ethnic minority people report worse experiences than White British people of almost every general practice dimension. And ethnic minority people diagnosed with cancer saw their GP several more times than White British people before they were referred to a hospital.

An inequality in overall health

It isn’t just inequalities in service; there is inequality in people’s overall health. However, the race report argues that ethnicity is not the primary driver of health inequalities in the UK. Ok, let’s unpack that a little. It is well known that ethnic minority groups are up to six times more likely to develop diabetes than White people. Sure, we could focus solely on diet and lack of exercise. However, there is a need to look beyond that. Patel and colleagues argue that socioeconomic barriers to healthy behaviours can play a factor. Barries such as prioritising work over physical activity to provide for the family, different perceptions of healthy body weight, and fear of racial harassment abuse when exercising.

Finally…

This has been a long one, folks; thank you for sticking with me along the way! I have analysed the identical spheres the race report looked into and have hopefully shown a snippet of how racism is still deep-rooted. And that is all I have been able to do, offer a snippet. The race report is 258-pages long, and how it provides no evidence of actual institutional racism is beyond me. Sure, it agrees racism exists through individual and interpersonal prejudice and discrimination. However, it also exists through institutionalised and structural forms of racial and ethnic exclusion and marginalisation. Ethnic minorities remain structurally disadvantaged, more likely to be concentrated in more impoverished areas, and experience more negative outcomes with their engagement with and employment within key social and political institutions, including the criminal justice system and labour market.

We mustn’t bury our heads in the sand and deny all existence of institutional racism. We need to acknowledge it, see the inequalities that exist, and understand our unconscious biases. Only then can we better frame and deliver a positive vision for the future and fight discrimination whilst upholding equality.